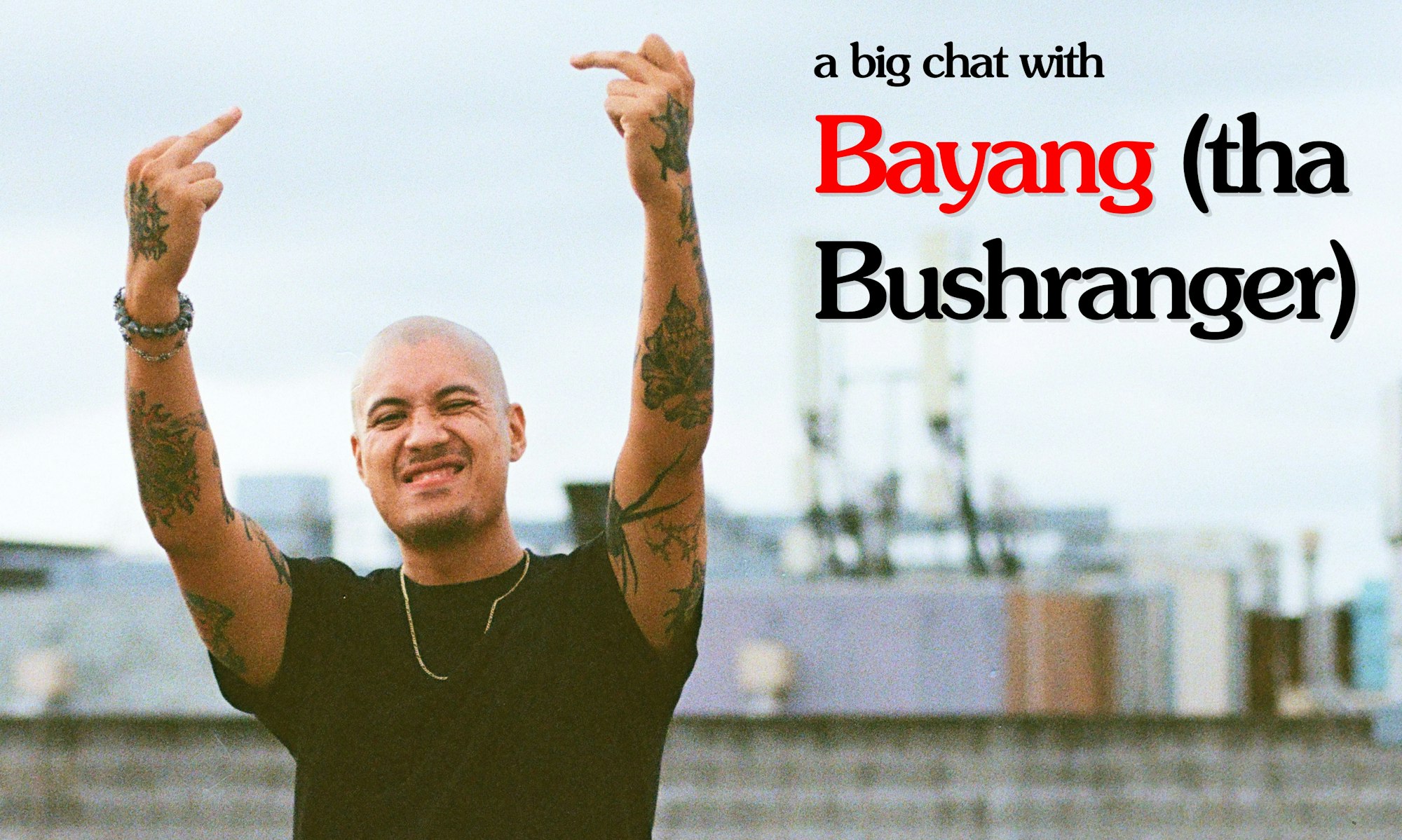

"Believe in your shit!": A Big Chat with Bayang (tha Bushranger)

Bayang (tha Bushranger) is the alias of Harry Baughan, a member of the currently dormant "anti-colonial shoegaze post-dystopia black metal" group Dispossessed. Bayang is a rap project which allows him to – in his own words – give "a face and an aesthetic to this mongrel culture that me and a lot of my friends came out of in Western Sydney". Originating from out of the Sydney DIY hardcore and punk scene, Harry has become a significant force in Western Sydney's exciting, thriving, and mercurial landscape.

I sat down with Harry at the Canterbury League Club in Belmore to talk about where he came from, his creative process, and the impact of being in a radically successful DIY band at age 20.

* * *

I was really keen to start with Dispossessed. Or actually — I was really keen to start even before Dispossessed. What clicked you into music at a community level? When did that happen?

I guess Black Wire [a DIY venue on Parramatta Road in Annandale that operated from 2010 to 2017] would have been the start. I remember I was just a ratty teenager, like most people are — would have been 15, 16. And I had this friendship group that I hung out with — smoke weed, get drunk, talk shit. And there was this other guy in the group, [who was] also called Harry, and he was also really inspiring. I ran into him on the train one day, and he was like "You should come to a gig at Black Wire sometime!", and I was like, word! So I did. I dragged a few friends along. We saw a few punk shows, saw some shows that probably challenged us too much. Like, I remember seeing like my first noise show there and being like, "Bro what the fuck am I doing here?" But yeah, that's where I met a lot of people who I'm still friends with today.

That's where I met Josh [Dowton, from Bract], and A'isyiyah from Arafura. Saw them playing in Palmar Grasp back then. Saw Josh play in ACHE and Ted Danson [With Wolves]. Yeah, just made a lot of friends there. I always tell people that Josh used to get me drunk. He was actually very responsible and didn't get me drunk, but I did steal beers a lot. [But then] he'd go "Harry! Can you do the door?" — I felt so elated!

I always had an interest I suppose. I just followed my nose, started a few shitty high school punk bands that never went anywhere. But I guess Dispossessed was like the first real project, the first time it was taken seriously.

Were you punk adjacent before you got into the Black Wire scene?

Oh, absolutely.

What sort of stuff were you listening to?

Heaps of Black Flag. My dad was born in DC, so he put me onto a lot of the DC scene — Fugazi, Minor Threat obviously, Bad Brains, Dischord Records in general... And then after he showed me the basics, I kind of just dove in headfirst and got way more obsessed with it than he ever did. Because he was kind of like, "Oh yeah, that's cool", but he's more into The Go-Betweens and The Church — that sort of music, you know? Whereas I fully got into hardcore — had a mohawk at 16, snuck into an Anti-Flag show when I was 17... who were not very hardcore! But you start somewhere!

So yeah, [it was] just me and my friends. I was lucky to have three or four mates who were also ravenously into it.

Out of curiosity, DC / hardcore ethos and politics — the Fugazi/Dischord system that they had set up... were you aware of that at the time?

Absolutely. That's what appealed to me so much. Being young, I was just so full of rage, right? Like it fucks off all this other bullshit and wankery. Doesn't associate itself with any of that at all. I was so into that. I remember seeing Minor Threat going "We're never gonna do a show for more than 5 or 10 bucks!" Like, those Black Flag interviews where they're going, like, "It didn't matter if three people came out, we'd still play the show!" That appealed to me hugely.

When you're young and finding yourself, I just felt so alienated from what everyone else was listening to — and maybe what was playing on the radio. And then when I found that I was like "Boom! This is my shit!"

So Black Wire would have been dynamite, to stumble into that...

It was me being like, "Oh wait! this shit's still going on and it's, like, right here!"

Yeah, it was cool. We were all pretty broke. So [because of Black Wire’s affordable cover charges] we could afford every show — or Josh would just let us in [if we couldn't]. Saw a lot of bands that I didn't know, it was hectic. And just, lucky to have such a supportive community I suppose. Those people took us under their wing immediately.

So — first bands, couple of school acts. Just garage-y sort of things?

Yeah, straightforward hardcore punk, Black Flag-y, not very good. There's an mp3 lying around somewhere. It was like one song. It was called "I'm A Disease", which is just me saying "I'm a disease, I'm a disease, I'm a disease, I'm a social cancer"... nothing too fancy!

But then along comes Dispossessed. And your Australian Music Prize shortlisted album... that was kind of, I guess it was the culmination of the band. What's the status of Dispossessed?

That happened at the start of COVID. So I guess that's towards the end. Yeah, we haven't played since then. People felt certain ways about it. I definitely felt a certain way about it, there's just so much baggage — let's just put this to the side for now. Doesn't have to be goodbye forever. But I think we all kind of had the desire to do other things. Dispossessed was really all-consuming.

Dispossessed is a very deliberate beast...

Oh, yeah, absolutely.

As a bunch of 19-year-olds, what made you go "We want to do this, and we really want to have a very specific sort of mantra about it..."

I guess we were like... that teenage fury was still there. Except this time, it had like a bit more knowledge behind it. And at this point, I'd seen, like, how many fucking grindcore bands and how many ironic crust-punk bands. And there was just this staleness in the punk scene that I was just so sick of. And then that was combined with this increased awareness...

You know, at that age, you start to get the language to describe what's happened to you in the past, you know, so at 19 you start being like, "Wait, hold up, maybe I did grow up in a quote-unquote 'working class' community. You know, like, maybe I do come from a colonised background. What does all this mean? And you're wrangling with it. It's fresh. And so there was just all this anger at staleness, and the unchangingness in Australia in general. Seeing that in spaces that were supposed to be radical just pissed us off.

There was no expectation when we started. We were just like, "Let's make a band. And let's make it angry. Let's piss off a few people. Let's ruffle a few feathers. And let's be loud, you know? And let's not be straightforward.” And then, the next minute...

How many "big idea" chats were there about the band?

Oh, ten billion! Like, too many! Too many.

I still think back to how I must have sounded back then, and it lets me interact with 18-year-olds with a bit more grace. I've got younger siblings all around that age, and it's like, "Yeah, all right. Well, maybe it is important for you to think for a little while that you do know how the world works."

Creates the humility, right?

Yeah, absolutely. Like you can't force that. That's not genuine.

At the time, you were all based whereabouts?

I was in Burwood at the time with my family, Serwah was in Pendle Hill. Otis was in Bondi — we were from all around the joint. And it was kind of like a revolving door. We had Jarred join, he was from Riverwood housos. We had other people who were joining from rural areas. It was a big mix of influences. But generally, there was this sense of "we're from the outskirts". I was living in Burwood at the time, sure, but I'd grown up in Bankstown. And even then, Burwood still felt so different to the Inner West in a Newtown kind of sense, you know what I mean? And so we were like, wait a second, y'know, we're rubbing shoulders with these indie bands whose dads bought them amps, and got to go to music school. And we're just pissed off kids from shitty neighbourhoods and pretty fucked up families who like hardcore. So yeah, I guess there was that distinction kind of happening.

When you started playing shows, you'd already been exposed to DIY. Did you want to go down the road of playing in traditional venues? Like, was that something you pursued?

It's not something that I ever expected to happen so quickly. We started off playing in DIY venues, because it was like "this is where we are" — like, we were all going to DIY shows. So we're like, "Well, who else are you going to ask but the cunt next to you? Hey bro, can you hop on this show?" But then at some point. Like, VICE picked us up, and we started getting a bit more publicity. And we start getting contacted by, at first, the Lansdowne, which is cool, and it's really exciting — Newtown Social Club... and then you blink, and it's like, Dark Mofo! And offers to play other festivals, and offers to go overseas that we never took up, on real festivals. It was just "Where the fuck did this come from?" But like, none of it was deliberate.

We definitely had goals. We were very goal-oriented, and we were very driven. "By the end of the year I want to have done this", but then like, none of us expected that to be [achieved in] two weeks! And then it's like, "Oh shit, now what do we do? I'm 20 and I love smoking weed every day, I'm not used to this!"

So that all starts to happen. You're picking up steam, you're working on the craft... were there any surprises from that process where it didn't turn out the way you thought it might?

Oh mate, if you've done your research you know absolutely it did! The whole thing imploded. And I guess like people have heard that story a billion times now. But yeah, I don't know. Just — toxicity, abuse — all kind of combined with like, youthful anger, ego, our first taste of fame, clout. Like, it made me sick...

It made me sick in retrospect, because it definitely got to my head, as a 20-year-old.

Why is that?

Like, you walk around and — like, we weren't famous in the same way that, like, Midnight Oil are famous, but I couldn't go to any of the places I was going with someone stopping me going "Oh you're in that fucking band, hey!" — stopping and having a chat. Go to some random party where you don't think you know anyone. Someone stops you: "You're in that band, hey!" And yeah, it got to my head.

Plus, we were kind of considered spokespeople for the movement, as well, like these older mentors, who I don't begrudge in any way, really encouraged us to kind of step up and speak. But you're a kid! And you really don't know that much shit. And especially like that kind of era of Instagram, Twitter, etc. Like, it gets so tied up in internet clout, and you're like "Maybe I can measure the success of the message in how many followers I'm getting?" or whatever it is. And counting how many likes a Facebook page is getting, you know, and who's accepting my friend requests. And it was all bullshit. So that combined with the specific toxic relationships within the band made for a particularly powderkeg kind of situation. That blows up. Didn't expect any of that. I pulled away at that point, because I was like, this is starting to make me sick. I don't want anything to do with this. Sick, both metaphorically and literally. This lifestyle, I was not doing well with it. I was like, "I need to get out of here before I literally fucking blow my head off", because that's what I saw myself going.

Our last show at the time — I just look back on and go "Damn! That's the most depressed I've ever been" Like, look at little 20-year-old me — oof, he was on the edge. He's malnourished. He's skinny. He's got bags under his eyes. You know, all his relationships are falling apart.

So yeah, that happens. We revived it again down the road, with a new membership, and had a bit of fun. But yeah, we put it to the side, after recording another album, kind of free up some space to finally pursue stuff for passion's sake.

It doesn't seem to me that you've decided to quiet down — in terms of your voice, that's not the lesson that you took from the experience. How have you changed your approach in terms of "speaking to the times", to speak very broadly…?

Hugely. The conversation style is completely different for me now. Whereas then, I think the goal was to be inflammatory — and that's incredibly useful in certain instances, but I think around that time, we all kind of saw the emergence of maybe like clickbait-style promotion, which I think other musical acts started to lean into. And we just kind of went, "How sincerely are we saying this? And how much are we doing it because we know it's going to garner a response?" And so, getting older, it's now become, "Well, who am I having the conversation with? What's the goal?" At the end of the day, if you want to be successful in some kind of radical movement — you can't just kill everyone! Yeah, surely some people are theoretically going to be up against the wall, right? But I think neighbourliness has become a big one for me.

And that's, again, going back to a lot of the mentors from that time, who have completely changed my perspective, like coming into that movement. And they were like, "No, no, no, we're trying to welcome people to Country. The problem is that people are rejecting our invitation." And therefore this kind of sense of harmony, and being in sync with the land, being in sync with the culture, being in sync with humanity and divinity and that kind of stuff all goes out the window.

It's hard to summarise but yeah, it's completely different now. It's still extremely radical. The end goal is still the same, but I think the means have changed. For example, I work with a lot of bogans — love 'em to bits...

Worksites, right?

Yeah! Mad cunts. We're from different worlds. Yeah, they're like 40, 50 years old, from Maroubra — I'm not from Maroubra, I'm from Bankstown! And like, recently, like, I had a mad conversation about Palestine with someone at work who was like 50, 51 years old, that I could not have envisaged myself doing at the age of 20. Because I would have just been gone. At the end of it, he literally went "Bro, actually, this is the first time I've like sat down and thought about this and realised that Israel is on the wrong side". He was like "Tacitly, throughout the years, I've always just kind of bought that narrative. And then now I realise like 'Shit, like, you can't do this!'" And I was surprised. Because that wasn't my intention in our conversation. I was kind of just talking to him and trying to be honest, and trying to be respectful. And then he comes back the next day and he was like "Bro, it's about Palestine!"

Is part of it finding the restraint to let the conversation happen in its own time?

Yeah, absolutely. And you've got to meet people where they are. I think that's a huge part of it. You have to push back on things, and you have to be honest, you have to be true to yourself — but at the end of the day, people are only going to be coming from so far.

It's like being multilingual, you know what I mean? I talk about things in a certain way with people I grew up with, but I talk about in a different way when other people are around because I want to include them in the conversation. It doesn't always work. I'm not saying that's the solution, but the approach is different.

Your delivery method is very much changed in terms of the work you're creating as an artist. How did that come about?

Like, doing hip hop?

Yeah, but it's much more direct and the words are front and centre. And I know that the lyrics in Dispossessed were always really important to you, but...

Buried in the mix, yeah.

Totally. It's very textural, you know, you go digging to find the lyrics. Whereas [with Bayang (tha Bushranger)] the lyrics are right here. What was the thought process in getting to that?

I was always interested in hip hop. Like, that was always a big conversation as soon as Dispossessed started, like, we're all hip hop heads as well. Like, it was just like, this Western Sydney thing of being like, "Well, I'm a freak, so therefore, I've taken everything from everywhere." You know what I mean? Because there wasn't really a space for Western Sydney freaks at that time. Like, there were Western Sydney goths, you know — we liked goths, but we weren't quite goths. We liked skate punks, but we weren't quite skaters. We liked graffiti, but we weren't writers. So we were just grabbing shit from everywhere.

From day dot, we were always listening to hip hop, and towards the end, like... we would finish practice, and me and Jacob [Cummins, from Dispossessed] would hang around, we would just fuck around and spit over some beats, and that kind of stuff. And then we started going "We should record some shit!" He'd produced a few things, he had since being a teenager, but had moved away from it a bit...

It just seemed like an endless realm: that was the appeal of hip hop. I was like, "Whoa, there's so much potential" — to twist, play with, broaden, you know? It was like rediscovering that passion for creativity again that I had at the start of it: "Oh wait! I didn't realise I had all of these ideas in the back of my head, that now have a possibility of fruition." It just made sense at the time. I guess there were things bouncing around in my head that didn't quite translate into death metal songs.

We talked about lots of "big idea" chats going into Dispossessed. Did you have an articulated framework for the Bayang project? Was it that from the beginning, or you just spitting over beats, or ...

I was just fucking around! [And then] Serwah from [Dispossessed] introduced me to Utility. He's incredibly crisp, and professional. So like, you can come in there with the roughest idea, and he knew how to make it sound good. So that was really fun.

Was he coaching you on your delivery, as well as producing?

Yeah, he was like, "Try this! try that!" — but also throwing ideas at me, and putting songs in front of me that I hadn't really heard before. Opening my mind, and broadening my taste. You know — you put a microphone in front of me and a beat, and I'm going to try my best. And then as I did it more, that's when I started to go "this is what I want to do. I like this, this little thread.” I always had an inkling that I wanted to be on the leftfield. But what “leftfield” meant made more sense the more I did it.

You don't want to sort of overstudy it, right?

"What does it mean?" [laughs]

Is there kind of a stated purpose behind the Bayang project? Not that you'd have it written up as a mission statement or anything — but do you feel like there's something that you intend to achieve?

Something that's been on my mind recently is giving a face and an aesthetic to this kind of mongrel culture that me and a lot of my friends came out of in Western Sydney, and in Sydney in general...

Do you feel like you put on characters when you're doing this?

I try to be myself. I would like to get better at performance. The more I read interviews with authors, the more they seem to talk about "embodying the voice" and how important that is. And so I've been thinking about that a lot. Going "OK, it's not always me, me, me, me" — in fact, that's probably kind of egotistical. Like, coming out of yourself. And, trying to write a narrative about other things and other people is important, I think. I'm still getting there.

I asked the question because there's a lot of range in what you're putting out. And sonically, obviously, you're working with a lot of different producers. It feels like there's multitudes that you're expressing, probably inspired by the sonic environment, but it feels like there's lots of different shades of Harry.

Yeah. For example, the Bract project, had me being really interested in religious fanaticism, like à la Dune and Lisan al-Gaib. But also the history of religion itself — images of Jesus flipping tables in the temple and that kind of stuff, liberation theology. And I was like, "OK, now I've got a space to kind of follow this and flesh it out." So I guess it has multitudes just because I try and find the thread. And then building on that.

Are you writing in a book first? Or do you tend to wait for the sonics to play against?

I write in my Notes app a lot. But I think lately in the past, maybe even month, I've been moving away from that, and waiting to hear the music first and then letting that dictate a bit more of what is demanded. Feel the push back.

Can I switch gears a little bit and talk about the economics of being a musician. Firstly, do you have any aspirations for yourself in terms of what you would hope music to be able to do? Where does it sit within your broader... 'lifestyle' feels like a corny word, but...

Yeah, I get what you mean. I'd love for it to bring some money in. But I'm not hanging my hat on it. I'm doing it regardless. My biggest goal for ages was to go overseas with it, and then I did that last year, so now it's kind of like "Oh, now what?"

I think I'm trying to let myself dream a bit bigger, and get ambitious again, without it necessarily being about ego, and feeding my sense of self. Just letting it have a chance to stand on its own two legs, giving the project a fighting chance. So yeah, it'd be cool if some money came in, I'd love to just go overseas and do that. And I'd love to start working with artists that I admire. That's stuff I'm looking at this year — people overseas. I'd love to be, maybe like, more of a mainstay in the Southeast Asian scene, I think that'd be cool. I'd like to collaborate with people more. I'd like to… be a bit of a problem, you know, keep going... there's so much crazy shit happening now! You just really, really want to be part of it, because it speaks to me — like, so deeply.

It's been a bit hard to allow myself to dream big in the past few years. But one of my oldest mates is, you know, my quote unquote 'manager'. It's really just an excuse for us to work together and talk every day, but he's been hugely helpful.

This is Dom [O’Connor, who fronts Organs], right?

Yeah. One thing he's good at his being like, "Listen dickhead, dream bigger! Get hungry, bro!" It's good, it's good to have him there, pushing me and being like "No, don't short-sell yourself."

So you've been mates for ages...

Yeah, years. He was one of the first people I was going to Black Wire with!

When did you go, "OK, let's turn this into a business relationship as well as everything else"?

I guess a few years ago, after I'd been playing around a bit. I went, "I want to start taking this seriously". And I think that year would have been right at the start of COVID or something. Like that year, I started being like "OK, I'm going to Melbourne every two months, just to record" — like, not to party. Just because I really enjoyed working with people down there, and I felt like it came naturally. So I started going every two months. "Alright, I'm gonna start pushing this a little bit more." I did this for a year, and went "Holy shit, did you forget you have a full time job? and a life?" I was like, "There's only so much I can do".

And Dom has been working in music as long as I've known him, but had recently really fallen out of love with it. Our point of butting heads growing up was always that he had a bit more trust in the music industry than I did, whereas I really fell in love with the DIY side of things. He ended up getting really burned. Like — it's his story to tell, but I just saw him become just so wrecked. I felt so heartbroken seeing such a close friend lose what was most dear to him, which was music, like it always meant everything to him. And then I just went "Maybe it'd just be fun to ask him to help me out, and he can rediscover his fire."

And so I asked him to help me out... again, it's an excuse for us to talk a bit more, and hang out, and get a couple of beers... and he ends up being a gun! So hungry, and tireless... it's such a thankless job at this point, like I really cannot give him that much monetarily — I just have to thank him every opportunity I get.

But yeah, there was no other way to do it. I wouldn't have asked anyone else. It just made sense. He was someone who I've cried with, fought with, laughed with — we've been through ups and downs, we've seen each other in every which way. It just made sense. He's the only one that can handle me. Because I can be a shit! But he's just like, "I've seen this before..." [laughs]

So you're talking about that year of all of those Melbourne trips. I'm taking from this that you're scheduling your activity? Do you have a rigour that you’ve developed for your creative process? Do you make sure that you're doing X amount per week? How does it work?

I do now. I didn't always. Discipline and routine were very hard for me. I looked back at the times I was unemployed and I'm like, "Damn, I had all that time but I did fuck all!" — it's because I had no routine. Working full time, I'm not gonna lie, it worked really well for me, because it made me realise that every fucking minute counts, you know what I mean? You have to get those bills paid, right? But you want to do something, you have to slot that shit in. Otherwise, it's gone, like sand between your fucking fingers, or something else is gonna come up. You need to be deliberate. You need to be on top of it.

Therapy also helped me with this. And getting into physical activity — I was doing Muay Thai for a few years. And that's when I realised discipline... it's the little things, you know? It's showing up. It doesn't have to be successful. But doing your drills is important, and the same thing is true of creativity. People who play guitar practice their scales. Is that writing a mad monster riff? No, it's practising your scales! But you've gotta know those fucking scales!

And for me it's about making sure I have time to write or produce at least a few times a week. At the moment that looks like — this morning, I got up at 4am, because I start work at 7am. Worked on a beat for like an hour and a half, did some writing and then went to work. I'll try and do that twice during the week, and then another time during the weekend. And then slot in some studio time as well.

Now it's like: OK, Mondays are the days I cook dinner. Tuesdays are the days I do laundry. Wednesdays, I get to go lift weights.

A man of routine!

Yeah.

And you've learned to trust the routine…

Oh yeah, absolutely. You know at the start, it's scary. And then a year afterwards, you look back and you're like, hold up, I've come so far! From doing my drills.

And it's not obvious, like in a week-to-week, or even a month-to-month, but at some point you're like... not to be competitive about it, but you know, to be in the sportsman mindset — I am putting in so much more work than everyone else around me. Of course it has to pay off right? It has to mean something. Not immediately, not necessarily materially — but in terms of your craft.

There's being disciplined in a more social creative construct. You know, there's weekly rehearsals for example — that's a form of routine. But the difference of creativity in solitude and being disciplined with that, compared to doing it with other people around you. Are there any different aspects that I guess the solitude thing has brought to you...?

It's so much easier! Like you get into your late 20s and getting five people into a room is like herding cats. You really only have yourself to be accountable to. And I guess when I was young I thrived off of being accountable to other people. And being like, "I have to show up to prac on time". Because four other people are counting on me. But now it's just me. It's just a question of when I wake up in the morning, it's like, "You've set your alarm for this time... you may as well get up and do what you said you were going to fucking do! You're going to be tired anyway!"

But yeah, Nerdie [of 1300] told me recently: "If you want to go fast, you go alone. If you want to go far, you go together." And now that's sitting on my mind, because I'm like, it's been so easy to go by myself. What does it mean to go together, when you're a rapper?

Speaking of collaborative projects, one that made a whole fucking load of noise was the Bract record...

It definitely was noisy! We knew that shit was never going to be a commercial success but like, it's about cultural impact. We knew it was going to speak to someone — speak to some people. And it might not be a broad set of people — but the few people that it does speak to, I feel like were gonna feel it deeply. And that's what it was made for.

So obviously you've known Josh for ages. So you've been around that crew — the Teddy Ds Cinematic Universe [the members of the no-longer-active Ted Danson With Wolves are in a million bands]...

I finished uni, I said "Fuck this, I need a break". I went to TAFE, and the first day of TAFE I saw someone in a Passing t-shirt and went "Fuck!" and ran across campus and went to talk to them. And it was Mikhaila, from Bract. And we had talked a few times but had never been best mates or anything. Before long, we're spending every day together, we end up working together for a few years, and I get to know them in such a more meaningful way. And because of that, I got to kind of reconnect with Josh again, who kind of became an acquaintance as I got older. And suddenly we're great mates again, and hanging out all the time. We just kind of went — "let's make some hip hop!"... I mean Josh is a huge hip hop head... that's no secret!

I don't know where it started, but like me and Mikhaila would have been hanging in the air — because we were doing high rise work — and they would have been like "Do you wanna make an album?" I would have been like "yeah!"

The Bract collab came out as a fully formed piece — there might have been a teaser track or something like that, but it's clearly: it's the album. But you've taken a very different approach with the Bayang project: apart from the EP that you recently released, there’s been a lot of drip-feeding [one or two songs at a time]. What's the thought process around that? You're also going all-streaming. What are your thoughts around getting the music out there, and the manner in which you've done it for the Bushranger stuff?

Sometimes, it's just about hearing a song and being like, "Yeah, this deserves legs. Let's give it a crack."

The Antarctica mixtape was just literally a collection of songs that I'd had lying around for ages, like, since those days that I was going to Melbourne every two months. There were 15, 16 songs, and then it became a matter of finding the thread. And I found this fun little pop thread through it, and I just went, "OK, let's just throw it all together. And it doesn't have to be a cohesive project, but I want them to have a fighting chance.”

Guild was all recorded in one night, so there wasn't heaps of thought — it was like, we just recorded all those tracks and went "Yeah, let's drop this shit". A lot of it's just cutting teeth, a lot of it's just trying something out, liking it, and liking it enough to be like, "Yeah, I think this has something to say". You know, like, I think it's necessary that this is part of Sydney hip hop canon. Like, I want this to be part of the Sydney hip hop canon.

That's the ambition.

Yeah. Like, I want people to know that this kind of music is being made right now. And, looking back in the future, I want them to know we were doing that now as well, you know?

On the legacy thing, how do you make it so that your work isn't just going to become part of the hard drive detritus? We're only 10 years into the streaming era, and I already see records that came out then, and maybe the label got bought by another label, and... "Oops, we accidentally lost an item in the catalogue" and then you can't listen to that music forever. What are your thoughts around the lasting legacy of your recorded work? How would you like it to be accessed and remembered?

I think physical media is so important to me and a lot of the people around me. I don't think my thoughts are fully formed on it yet. But yeah, you're right, the streaming world is so ephemeral, right? If someone just switched off the lights tomorrow, what does that mean — that the music won't exist anymore?

For the Bract record, we made sure to do cassettes, and we're currently pressing LPs which is exciting, because I've never pressed an LP before. Working with Content has been mad because Neil has a lot of fun doing stuff like DVDs and, again, cassettes and... you know, just like various forms of physical media. It's important! It's important to be like, "Aw shit! this shit's real!" And people want an artefact, I feel. You know what I mean? It made me feel more connected to these projects, like having an Extortion live tape and going "Whoa, there was only 20 of these!" I don't know, I feel like culture has to be somewhat material... otherwise, it can just be like wispy fuckin' data.

But you can't just hate on everything, you have to be part of the conversation. Like you have to react to the world that's changing around you. But at the same time there's potential, right? There's potential in this weird internet era — get playful with it! Get cheeky with it.

How do you approach the live aspect of what you do? These days "live" for projects that have been born out of studio projects, it's an interesting one. And I know that a lot of the time for solo shows you've got someone just cueing up tracks with you. I mean, you've done it all — it's not like you need to be told that it's fun to sing without a click track. But where are you heading with live?

Oh, man, like I'm chewing on that hard, right? Last month I did five shows in the month. And they were all really fun. But by the end of it, the one thing I knew in my mind was: I need to completely destroy this live set. What I'm doing right now, is not speaking to me, like whatsoever. Like performing the songs with the beat playing in the background? I don't know where I'm headed, but I know I'm done with that. It might mean crafting some songs only to be performed in a live setting. MCing has been a really cool experience, because you're able to curate an experience over that 45 minutes, and now it's got me thinking of the set more like that: where you want to begin, what do you want to have happen in the guts, where do you want to be by the end? You know, what's your big finale? What's your drama? I want to get performative! That was the big attraction to me and metal, you know what I mean? Like, seeing these black metal bands come out, and like garments and just encapsulate you into this world, you know? Like, just absolutely swallow you until you forgot that the outside world existed. I would love to be able to do that with hip hop, with this specific kind of world that I'm trying to build. I don't know what that looks like right now. Literally, like two weeks into this.

But I've got a big break from shows. And then the next show after that is likely going to be a Bract show, which I feel like leans into that anyway. So it gives me a lot of time to think about that. It's on the forefront of my mind. It's keeping me awake. It's annoying me. It's a thorn in my side!

There are lots of people that feel like the only way that they can really give music a red hot go is to fully immerse themselves in what we refer to as the "industry". Which isn't to say that that's not a right path, for some people that works really well. What are your reflections on what's gained and what's lost going DIY or going industry, in both directions — not to cast any judgement...

I guess in DIY, you've got this absolute creative freedom. I think that's worth more than anything. Like, you don't have the bottom line hanging over your head — you know, profitability and marketability. So you're free to experiment how you want. That being said, not all experiments are successful. Any scientist will tell you that — there are some experiments that blow up in your face, and it's pretty shit and smells bad. And also, you know, you can only go so far. That being said, I don't think that stops the craft from having cultural impact. And the DC scene, for example, is testament to that: how much money do you need behind it for it to happen, but a really really high impact.

That being said, we live in such a noisy world nowadays. It's so hard to cut through the noise, you know, and it's easy when you're speaking to your peers who are local. It's as simple as seeing someone in person and be "Hey bro, listen to my project!" "yeah cool!" When you know that there's like-minded people out there, in South Africa, or Atlanta, or some bumfuck town in Europe or something... you go "How the fuck do I reach them?? I know they're out there, I don't know who they are." And I think that's where some of the magnitude of industry can help, it's an amplifier.

And it's about, I guess, finding the right mix that works for you. At the moment I've got a distributor, thanks to Dom. And that means not much in terms of the creative process. It means I hand them the song and they go "cool, we'll try our best!" So I can basically hand them a steaming pile of shit and they'll go "cool, we'll try our best!" It's crazy, because people find you, in a way that I could never achieve as one person. And I was big on like, sending random emails on fucking Bandcamp and saying "Hey, what's up? What music do you like in your city?" Like, all of a sudden, we're friends.

For people who are reading that aren't familiar with what a distributor does, what has that sort of brought to the table for you?

When we have a release, we loop them into the process. They push it for playlisting, and that kind of stuff. They try and get it in the right places. We didn't put too much of a stress on getting stuff into advertisements and that kind of stuff, but that's like sometimes what they can do. But I guess they just push it. And through getting it into some of these curatorial playlists and editorial playlists exposes you to people that you might never have reached. And they take a small cut to do that service, from the money I get from streaming — which is nothing of note.

Because we're all getting so much from streaming...

Yeah. My 20 cents! If anything, I noticed an uptick after I signed on with them. Which was cool.

My theory is that I suspect that a lot of people aren't plugged into DIY simply because it's just not something that's ever presented to them. You know, they go "How do I get shows?" "Well, you get a manager, you get a booker..."

People think that the way to do it is to get signed to a major, and have this whole team working for you. And it's like — you can pursue a project of that style without doing all that. You know what I mean? And so many major artists are like completely breaking away from that route, because the industry is changing. If you want to look at it that way, it probably is more profitable helping you to be somewhat independent, and not to have someone like playing you're a fucking puppet when you know your shit's good. You know, believe in your shit!

It's been like a few years for the Bushranger project, right? Have you sort of bumped into any forces that have kind of been going "but you could be here if you only..."?

Absolutely. You know, people want to give their two cents. And I think earlier in the project I might have gotten a bit lippy, and I might have secretly been quite cut: "shut up! I'm doing everything I can! Fuck you, I'm working so hard! I'm working harder than I've ever worked in my life! Fuck you!" But like nowadays, on my good days, it's water off a duck's back. I'm trying to trust the process. I'm like, “I know what I'm doing. I respect what you're doing. And that's cool. And it works for what you're doing, go for it! That's not what I'm trying to do.”

There are those days where I'm feeling a bit low, and I doubt it a lot, and I beat myself up a lot, and I feel pretty shit. You always come back. I've gone through enough of those periods, countless times, to know that they're always temporary. Usually, you're always gonna learn something by the end of that as well. You go, "oh OK, what's my hang up this time? My hang up is, I don't know, maybe I wasn't as deliberate in my writing." And I'm feeling insecure, right? Because I knew I could have done better on this track.

Are you super self-critical?

I have been, yeah. I would say I am. I'm trying to be better at that initial trust. Especially when you're dealing with the new, or perhaps some uncharted territory. You just have to go, "Well, people aren't gonna have a reference point for it." They need to keep getting to that point, and then eventually you'll have something to show for and it'll make sense. Because that's what Dispossessed felt like: "We want to make anticolonial shoegaze fucking post-dystopia black metal"... people were like "What the fuck?? You're all 19! Shut up! Oh wait, this shit bangs!"

Eye on the prize!

Eye on the prize! And have those friends to call when you're feeling low on belief.

Why create music?

I want to be alive! It's me, it's the raison d'etre. I like to listen to music, to dance to music, to experience it... making it is just like a cherry on top.

So it just wells up from the experience of the music being around you, and then you get to do a little bit of it.

When you can see that you're having that same effect on other people, it's just like the best feeling in the world, you know? To be part of "it", you know, just part of the ecosystem. And be like "Oh shit! I'm doing it! I have ideas too!"

Those nights where we're up at 3am, we've made like five songs so far... but this sixth one was the one. And you're just sitting there 3am sleep-deprived, a ciggie hanging out of your fucking mouth, listening to this song being like, "I'm so glad this exists". This didn't exist before we did it. And now it exists. Just to participate in creation is like, it's so hectic. And there's so many different ways to do it, but music's mine, you know? And it's just like... yeah, I love it. Even if I never made a cent from this shit.

Is there anything else you'd love to get off your chest? I want to make sure we haven't left any stones unturned.

[thinks hard, and then addresses the mic] I'm broke as hell. I'm not very successful. But damn, this shit bangs! And if that's your only hang-up, fellow reader: like, fuck it! Who's to stop you? Know what I mean? Life's for living! Do this shit. Do it! Say what you gotta say.

I'm just stoked that there seems to be so much more of this happening nowadays. And even in the hip hop world DIY seems to be popping off heaps, the internet's doing massive favours for the weirdos and the freaks. It's hectic. So shoutout to the freaks!

- by

- Joe Hardy

- Published

- 22 April 2024

More reads

Welcome to SydneyMusic.net

Live music in Sydney is still clawing its way back to normalcy after a bruising decade of lockouts and lockdowns — but there's good stuff out there, and this site exists to help you find it.

"You don't need permission to do it yourself": Nick Ward on the Brockhampton Effect and Sydney's artist-driven future

"We're in this weird, fluid time in Australian music history where I feel like it's really fertile ground for people who have a really strong idea of what they want to do."

"The more you invest in the arts, the healthier the scene will become": Kirsty Tickle of Party Dozen on DIY and the dire state of arts funding

In the debut edition of our occasional Q&A feature, Kirsty gives us an intro to the community that Party Dozen came from, some thoughts on what can help our local community thrive more, and the importance of a broken PA in becoming a great performer.

"This place would not exist without the audience": Nick Shimmin of the People’s Republic on creating Sydney's most unique house shows

13 years. 120 shows. 1 living room. We caught up with Nick Shimmin of the People's Republic to talk about creating an alternative space for artists and audience to enjoy a shared sense of community.